Reposted from https://blogs.nasa.gov/mission-ames/2013/05/22/post_1369242690470/.

Line ops last night were cancelled due to a “no-go” by the telescope assembly subsystem. A problem had been found that could not enable observations tonight. It was a call the science team did not want to hear, but it was the right call. This exercised the reason why there is a “readiness review” before going out to execute a complex activity. A plan was put in place for the 1st shift when they get in at 7am (0700h) today (Wed) to address the problem and report back during the day. If all goes well, a crew-briefing will be scheduled again at 2130h tonight and we can resume line ops at 2300h.

If we were observing using a ground-based telescope, we watch the weather. A seasoned ground-based observer watches the humidity. You can often get obsessed looking at trends in pressure, temperature, etc. It’s important as you may need to replan your allotted observation time if you lose a night (or nights) to the weather-gods.When I assisted with a balloon launch last summer at Ft. Sumner, NM, we’d gather daily to address the winds. Winds were most stable at dawn so we’d have our “crew briefing” at 3 or 4am with readiness to roll out at 5am with the hope to launch in the next hour or so (it would take nearly an hour to do the roll-out of the balloon and the He fill). Yes, sometimes the call would be made at 3am for a “no-go” or even as late as right before the fill. And then you roll back the balloon to the hangar. Last Sept, we launched on the 3rd attempt. All rocket launches also watch the weather and have various sub-system “go/no-go” checks.

SOFIA ops are not so different from those other examples.

So, we replan again. We have three remaining nights left in the schedule, two this week and one contingency night next week, which now seems to be required. Also, we’ve started looking at the flights scheduled for next week, to see what tests planned in flight would supersede the line ops tests to allow to compress our “line ops” schedule. Now, this is a calculated risk since the purpose of line ops is to test the system end-to-end before flight. So essentially you want to run the key components you plan to test inflight on the ground first.

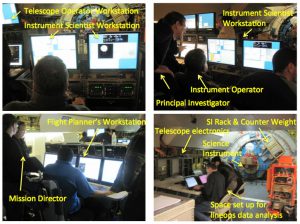

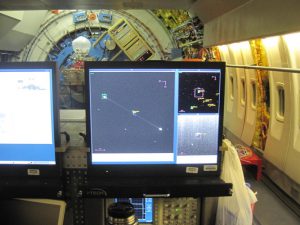

What are line ops anyway? It’s not as “dramatic” as the actual flight, but it serves very important purposes to follow our observation plan end-to-end, address timing issues, and most importantly, communication between people and communication between people & machines. The plane is towed out on the runway to a viewing position safe from any active runway traffic, and preferably in a location far from buildings or lights to obstruct viewing angles.We operate on plane-provided power. We command the telescope door to open,configure the telescope, check it out, power the science instrument, and start running through a series of discrete tests, some of which are to be run exactly on the flights, and other diagnostic tests that are needed that would otherwise take up the valuable flight time.

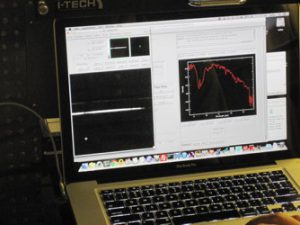

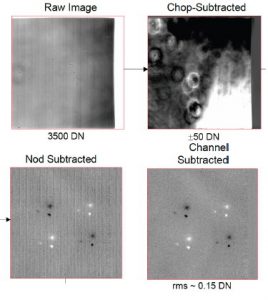

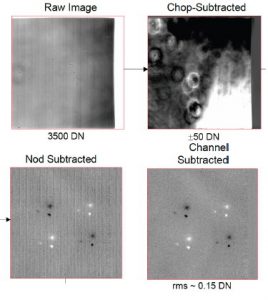

One of the tests we want to do is test the “nod” function of the telescope and how the data sets we collect affect our observing strategy optimization (ahem, improve signal to noise). In mid-IR astronomy, the sky background is “brighter” than our targets. In fact, we often cannot see our targets in the original raw data until we do a “background subtraction.” So we use the telescope’s secondary mirror to “chop” a source back & forth (as it would appear on our detector) at a fast rate. And then we would command the telescope to “nod” to a different part of the sky. And repeat the process of“chopping” and “nodding” over a pre-planned orientation, both “throw distance”and “angle.”

You can read more about Chopping at Nodding at Why Chopping & Nodding is needed for SOFIA FORCAST Observations.

An example taken from PDF on Signal to Noise Improvement by Chop/Nods sums it up nicely.

So we’ll be exercising things like this during the line ops, exploring the same technique for different roll angles because when it comes to your science target which can be anywhere in the sky, we’d like to understand the system performance and, if any, limitations.

So we’ll be exercising things like this during the line ops, exploring the same technique for different roll angles because when it comes to your science target which can be anywhere in the sky, we’d like to understand the system performance and, if any, limitations.

We have other tests planned like assessing the detector bias performance, looking at flexure of our alignment, particular for our grism mode where we have narrow slits, optimizing a new flat field technique, and running through the science scripts to checking for timing and fix any commanding errors.

So fingers crossed, we will get on sky tonight, on the tarmac at Palmdale, CA. The skies have been clear the last two nights, so we the weather gods have been kind. We now need the electrical-power-subsystem gods to be kind.