Reposted from https://blogs.nasa.gov/mission-ames/2013/07/26/some-insights-into-charon-and-what-roles-laboratory-work-play-in-new-horizons-science/.

These are talk summaries from the afternoon of July 24th at the Pluto Science Conference being held this week, July 22-26, 2013 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, MD.

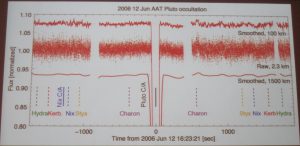

Marc Buie (SwRI) walked us through “The Surface of Charon.” Charon was detected by Jim Christy in April 1978, in what were originally dubbed “bad images” from the Naval Observatory, but not confirmed as a satellite by the IAU until February 1985. Charon is about 1 arcsecond from and ~1.5x mag fainter than Pluto. An occultation measurement in April 1980 confirmed the detection.

“Mutual Event Season” is when every half orbit of Charon passes in front or behind Pluto. This occurred over 1985-1990 time frame. For the specific orientation where “Charon went behind Pluto,” as observed from Earth, you can directly measure’s Charon’s albedo, the size ratio between Pluto and Charon and start deriving its composition. So, work in earnest to determine Charon’s surface started in the mid-1980s.

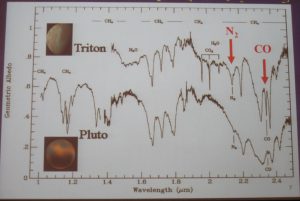

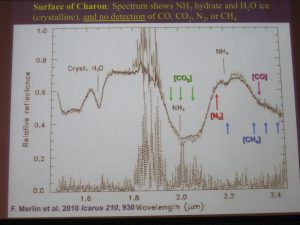

In 1987, Marc Buie and his colleagues got IR spectra using a single-channel detector and a circular variable filter, the best in spectrographs at the time, and this revealed Pluto’s atmosphere is methane dominated and Charon’s atmosphere is water dominated, and they do not look like each other.

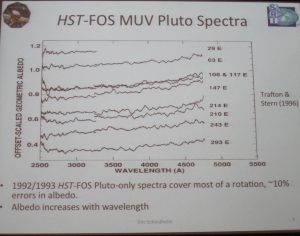

Hubble Space Telescope (HST) entered the scene and a series of observations of Pluto and Charon with HST started in 1992. The first rotational light curve of Charon was obtained in 1992-1993, indicating a 8% variation in the brightness, much smaller than that for Pluto and the data also confirmed that Charon was tidally locked with Pluto (just like our Moon is tidally locked with Earth, showing the same face). Marc Buie and his colleagues obtained HST NICMOS near-infrared spectrum in 1998 of both Pluto & Charon.

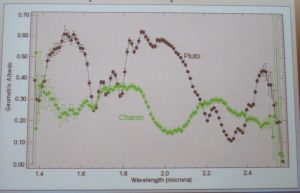

Comparison of Pluto and Charon infrared spectra, taken in 1998 at the same epoch (near in time with each other), with HST NICMOS (near infrared camera and spectrometer aboard Hubble).

A mystery. Spectra from Tethys, one of Saturn’s moons, has a remarkable agreement with Charon’s spectra, despite the bodies are of different temperatures and albedos? Will they have similar compositions when the New Horizons spacecraft flies by? The spectra is also not fit precisely with just water, so there is another unidentified species there.

Marc Buie was observing Pluto & Charon just last night (July23rd, 2013) with the Adaptive Optics mode of the OSIRIS instrument on Keck. This instrument achieves comparable spatial resolution as Hubble. At the conference, he showed off the latest image, “hot off the press.”

Predictions for New Horizons: Charon to have a heavily cratered surface with modest (subtle) albedo and color features. Expect to see differences between the Pluto and anti-Pluto hemispheres.

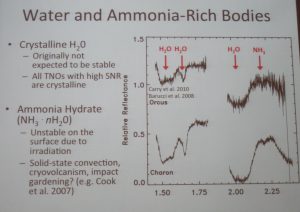

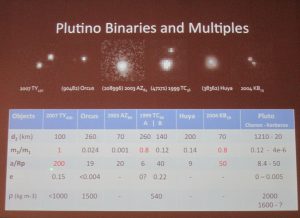

Francesca DeMeo (MIT) talk was entitled “Near-Infrared Spectroscopic Measurements of Charon with the VLT.” She began her talk stating that TNOs (Trans-Neptunian Objects) can be characterized as (1) volatile-rich (lots of N2, CO, CH4), (2) volatile-transition, (3) water+ammonia rich (H2O, NH3), and (4) volatile-poor (neutral to very red colors, maybe some water ice). No TNOs, to date, show evidence for CO2. Her analog is to Charon is Orcus, a TNO with its own moon Vanth. Both are water and ammonia-rich bodies.

Comparison of two water and ammonia-rich bodies: the TNO Orcus and Pluto’s moon Charon.

She observed Charon in 2005 using the VLT (8m telescope) with AO (adaptive optics), which separates Pluto. Her Pluto data is published in DeMeo et al 2010. Charon data was presented here in her talk and showed a comparison with Jason Cook’s data from 2007 and F. Merlin’s data from 2010, as they were looking at the same surface location. She is using the JPL Horizons longitude system.

For a review of Trans Neptunian Objects, she recommends Mike Brown’s 2012 Review Paper http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2012AREPS..40..467B.

Gal Sarid (Harvard) followed with “Masking Surface Water Ice Features on Small Distant Bodies.” Minor (icy) bodies (TNOS, Centaurs, comets) are a diverse population with varied size, composition and structure. Their surface compositions show evidence for water ice and other volatile species. They are understood to be remnants of a larger population of planetesimals. He stepped us though his thermal and physical model of a radius=1200km object to reveal the possible insides of these minor icy bodies. Observationally this could be tested by inspecting impact crater that could eject subsurface material. From his computations he varies the ratio of carbon (dust) to water ice to give predictions for water band depth. When he compares the colors of the computed spectra they match very ice-rich TNO bodies, but his work reveals questions to explain the B-R colors. The models may need more other ices (methane, methanol).

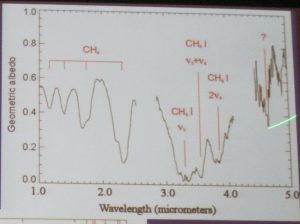

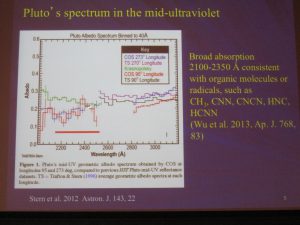

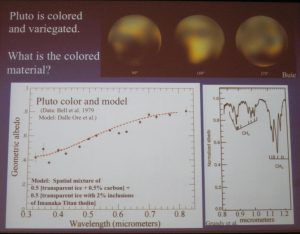

Reggie Hudson (NASA GSFC), a laboratory spectroscopist, presented “Three New Studies of the Spectra and Chemistry of Pluto Ices.” At NASA Goddard, they have equipment to test ices with their vacuum-UV (vacuum-ultraviolet). He showed 120-200 nm results of N2 + CH4 at 10 K. A second study was to measure CH4 ice in the infrared. CH4 has three phases: high temp crystalline T > 20.4 K, low temp crystalline T < 20.4 K, and amorphous CH4 forms around 10 K. He showed results for solid CH4 from 14-30 K over 2.17 to 2.56 microns and 7.58 to 7.81 microns. Their lab also has the ability to irradiate the samples, and when they have done so, certain phases recrystallize, but that is a function of temperature. Future work involves completing lab data of C2H2, CH4 and C2H6. Their lab website is http://science.gsfc.nasa.gov/691/cosmicice/.

Brant Jones (University of Hawaii) discussed “Formation of High Mass Hydrocarbons of Kuiper Belt Objects.” They irradiate their ices with a laser and their measurement technique is a “Reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer.” They have identified 56 different hydrocarbons wit their highest mass C22Hm where 36 < m < 46. Future work is to investigate PAHs, look at “processed ices” and study different compositions, and study exact structures.

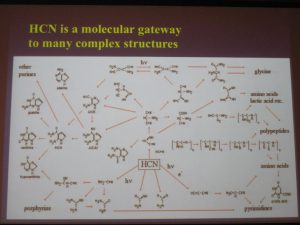

Christopher Materese (NASA Ames) spoke on “Radiation Chemistry on Pluto: A Laboratory Approach.” Reporting on their laboratory work at NASA Ames, in their setup, they radiate their ices with ultraviolet (UV). Now for Pluto, the atmosphere will be opaque (not-transparent) to UV radiation. Secondary electrons generated by ion processes, however, drive the chemistry and their energy (keV-MeV) is similar to that provided by UV radiation. He presented NIR (near infrared) and MIR (mid-infrared) spectra of his irradiated ices. They have completed over 20 molecular components. They also have a GC-MS (gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer) to measure the masses of the molecules they create.

The importance of laboratory work cannot be underestimated. It can help with predictions and equally important help with identification of molecules. Then once molecules and their abundances are determined, that can fold into more complicated models to look at volatile transport.