Reposted from https://blogs.nasa.gov/mission-ames/2013/07/27/pluto-exotica-atoms-pick-up-ions-bow-shocks-suprathermal-tails-x-rays-uv-airglow/.

The morning of the last day of this week’s July 22-26, 2013, Pluto Science Conference opened up the discussion with outer atmosphere (far out) and magnetosphere (really far out) talks.

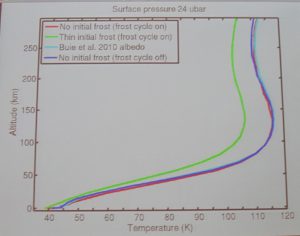

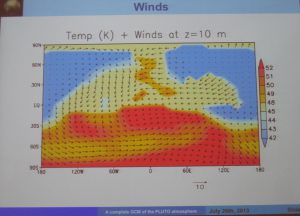

Fran Bagenal (University of Colorado) started the session with a talk on “The Solar Wind Interaction with Pluto’s Escaping Atmosphere.” Pluto’s interaction with the solar wind was first suggested in 1981 by Larry Trafton. There are two generally predicted regimes of what this interaction might look like: (1) Venus-like (small escape rate) and (2) Comet-Like (high escape rate). A key parameter distinguishing the two is what the atmospheric escape rate might be, that is, how many atmospheric molecules (assumed to be nitrogen) are escaping from Pluto, no longer being bound by gravity. Current estimates for the escape rate, based on a number of approaches, notably a recent one by Darrell Strobel (2012), have this number at 2-5×1027molecules/sec. This is large enough to suggest Pluto will appear to be “comet-like” in its interaction with the solar wind. However, we need to wait until 2015 for the New Horizons fly-by with their in-situ particle instruments SWAP & PEPSSI to make the interaction measurements.

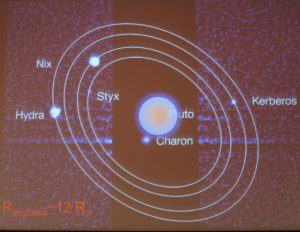

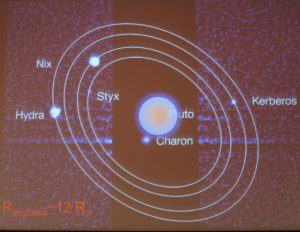

When describing the Pluto System in terms of solar wind interaction, Fran Bagenal showed this image, which superimposed one of Darrell Strobel’s atmospheres (characterized with an exobase at 12 Pluto radii). Pluto becomes a “large object” for interaction with the solar wind.

When solar wind particles (protons) interact with the Pluto atmosphere, their path through space is bent along the magnetic field lines, and to convert momentum, pickup ions (neutral hydrogen atoms from the heliosphere that undergo a collisional charge-exchange interaction with solar wind protons, get ionized, are “picked up” by the solar magnetic field) get tossed onto new trajectories. Those ions are charged and will begin to rotate and follow electrical field lines. Where do the ionized particles go? A weak magnetic field will create large gyro-radii of pick-up ions which can extend millions of kilometers upstream of Pluto. This is best modeled with a kinetic interaction.

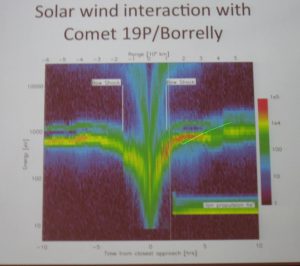

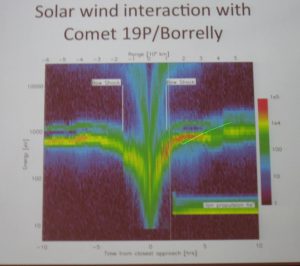

Peter Delamere (University of Alaska, Fairbanks) spoke in greater detail about “The Atmosphere-Plasma Interaction: Hybrid Simulations.” Plasma interaction is an atmospheric diagnostic tool. Neutral gases are not easily picked up, but ions and how they interact with the solar wind can be detected with in-situ instruments such Hew Horizons’ SWAP and PEPSSI. He discussed his model plasma interaction mode, which was validated using Comet 19P/Borrelly that had been visited by Deep Space 1 on Sept 22, 2001.

Example of Comet 19B/Borelly environment time vs. energy reveals the structure of the interaction between a comet and the solar wind. The X-axis is time from closes approach, with the Y-axis energy. The color code is the number of particles counted by the PEPE instrument aboard Deep Space 1. This is similar to what the data is expected to look at for Pluto when New Horizons reaches it in 2015, however, the solar wind at 33 AU may be more extended and more diffuse and therefore the signal strength (in terms of counts) will be much less.

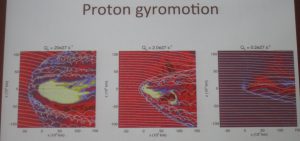

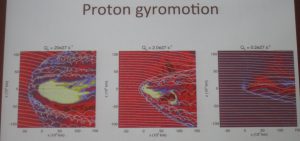

If we can understand where the bow shock forms, this becomes a diagnostic of the atmosphere, and if indeed the exosphere extends out to 10 Pluto radii as suggested by recent work by Darrell Strobel (2012) and other models, then this is a sizable ‘obstacle.’ But is it inflated enough to form a bow shock? Peter Delamere thinks so. He stepped us through a variety of simulations. One of the simulations predicts a partial bow shock. If you increase Qo (the escape rate parameter, predicted to be in the 2-5×1027 N2 molecules) or increase magnetic field strength you can create a full bow shock. Future work includes adding the pickup part of the solar wind model as input. If there is a very slow momentum transfer, perturbed flow could extend out to an AU.

Simulations predict all sorts of shock structures (Mach cones, bow shocks), but these structures depend on the escape rate parameter.

Example of a plasma interaction mode for three escape rates, decreasing from right to left. This is a slide in space of plane vs. distance from. The white lines are sample solar wind proton trajectories. The color scale indicates ion density. The solar wind (and hence, the direction from the sun) is incident from the left. Pluto is at (0,0).

Predictions at Pluto. He anticipates significant asymmetry. The predicted bow show could be as far as 500 Pluto radii.

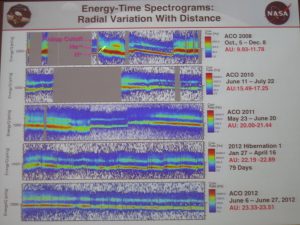

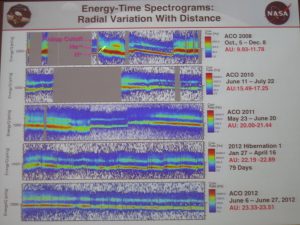

Heather Elliot (SwRI, San Antonio) in her talk “Analysis Techniques and Tools for the New Horizons Solar Wind around Pluto” described the New Horizons SWAP instrument and the different rate modes (sampling rate and scan types) it will be using during the 2015 encounter.

Measurement of the solar wind taken with the SWAP instrument aboard New Horizons during the last 6 years of cruise. This data set covers AU=10 (Saturn distance) out to AU=23 in 2012. The solar wind is mostly protons (H+). The second most abundant species are alphas (He++). The colors are the intensity of species. The vertical axes are energy per charge units and the horizontal axis is time.

Fitting the SWAP data to a solar wind model requires making adjustments for view angle and during the hibernation period, when they do not have attitude information, they have modeled the Sun-probe-Earth angle to estimate the attitude and this works well to fit their data.

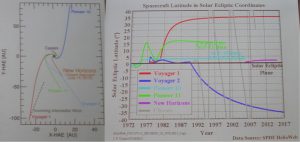

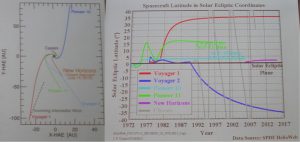

John Cooper (NASA Goddard) spoke about the “Heliospheric Irradiation in Domains of Pluto System and Kuiper Belt.” He is interested in computing the “radiolytic” dosage onto bodies in the outer solar system (that is, the effect of how molecules break down or change molecular band structure due to the influence of radiation, such as by cosmic rays, particles, UV, etc.). For this he needs measurements of the particle flux at large AU. New Horizons joins its cousins Voyager 1 & 2, Pioneer 10 & 11 and Ulysses in exploring the outer solar system.

Location of the NH spacecraft (orange on the left, purple on the right) for two different views of the solar system. Also plotted are deep space missions Voyager and Pioneer, among many. The left view is s top down view of the solar system with the Sun at (0,0), the axes are in AU, where 1 AU (Astronomical Unit) is the distance between the Earth and Sun. The right is a view of time vs. latitude for the crafts. Comparative data sets to New Horizons, which travels along the solar ecliptic, are Pioneer 10 and early Voyager 2 data.

He showed computations of irradiation dosage when applying those particle rates measured by New Horizon’s PEPSSI instrument and instruments aboard Voyager 2 and Pioneer 10.

He maintains a database of all particle instrument flux measurements at the Virtual Energetic Particle Observatory http://vepo.gsfc.nasa.gov.

Thomas Cravens (JHU/APL) with ”The Plasma Environment of Pluto and X-Ray Emission: Predictions for New Horizons,” asked “What happens when you get to within 1000 km of Pluto?“ Pluto is anticipated to be “Comet-Like” in its interaction with the solar wind, however when you get closer to Pluto (around 1000 km), it may more closely resemble “Venus-like” interaction. He is trying to compute where the charge-exchange boundary could be, probably around r~5000km. This is boundary between the kinetic (r>5000km) and fluid (r<5000 km) regimes, essentially probing the ionosphere regime of Pluto.

Switching to slightly lower energies, Casey Lisse (JHU/APL) gave a talk on “Chandra Observations of Pluto’s Escaping Atmosphere in Support of New Horizons.” X ray interactions (charge exchange, scattering and auroral precipitation) require an extensive neutral atmosphere, which is what is expected at Pluto. Interaction of solar wind with comets has consistently shown X-ray emission. He expects to see X-ray emission from Pluto. If detected it would tell us about the size and mass of Pluto’s unbound atmosphere. The best time to look for x-rays at Pluto is about 100 days after a large CME (corona mass ejection) event, which is about the time it takes for CME to get to Pluto at 33 AU.

He and his colleagues applied for, and got, time on NASA’s Chandra X-ray telescope. On Chandra, Pluto & Charon will appear to fill one Chandra pixel using the Chandra HRC instrument. He ended his talk suggesting that looking at background counts with the LORRI and RALPH CCDs might serve as a poorman’s x-ray detector. It is also possible that PEPSSI background counts could be used to infer presence of lower X-rays.

Kandi Jessup (SwRI) gave a talk addressing the “14N15N Detectability at Pluto.” We care about14N15N because it can be used to determine the 15N to 14N isotropic fractionation. This can help tell us about the evolution of Pluto’s atmosphere. Learning about Pluto’s atmospheric evolution history also provides vital suggestions for the evolution of equivalent TNOs (Trans-Neptunian Objects) and other objects in the Kuiper Belt, and hence, the outermost parts of our Solar System

The measurement will be the UV spectral observations during the solar occultation of Pluto by the Alice instrument during the New Horizons fly-by. N2 is the dominant absorber between 80-100nm. To identify the molecule 14N15N they use an atmosphere model from Krasnopolsky & Cruikshank (1999). That model does not have a troposphere. Next they need absorption cross-sections (a parameter that quantifies the ability of a molecule to absorb a photon of a particular wavelength) for 14N2 and 14N15N. 14N2 is the more dominant species and they are trying to find a very small percentage for 14N15N. Using these simulations they anticipate the Alice instrument will be sensitive enough to detect at least a 14N15N to 14N2 ratio of 0.3%. They will be look at the UV spectrum between 88 and 90 nm where the 15N lines spectrally shifted from 14N line. 14N15N to 14N2 ratio has been measured on Mars (0.58%), Titan (0.55%), and Earth (0.37%). What ratio will Pluto have? New Horizons data will hopefully tell us.

Randy Gladstone (SwRI, San Antonio) spoke about “Ly-alpha at Pluto.” Pluto ultraviolet (UV) airglow line emissions will be very weak, except at HI Lyman-alpha (Ly-a). Ly-a at Pluto could have both a solar (Sun) and an interplanetary (IPM/interplanetary medium) source. Ly-a should be scattered by Hydrogen atoms in Pluto’s atmosphere. He uses the Krasnopolsky & Cruikshank (1999) Pluto atmosphere model that predicts the number of Hydrogen atoms at altitude. There are several observations near Pluto closest approach planned with the New Horizons Alice instrument to measure Lyman-alpha emissions. This data will provide information about the vertical distribution of H and CH4 in Pluto’s atmosphere. Observation of the IPM Lyman-alpha source will be unique and provide important information to model Pluto’s photochemistry, especially for the nightside and winter pole region.

Randy Gladstone (SwRI, San Antonio) ended the session with a talk about “Pluto’s Ultraviolet Airglow.” He presented a model by Michael Stevens (Naval Research Lab), which has been used to explain the Cassini UVIS (Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph) observation of UV airglow at Titan over the 80-190 nm wavelength, emissions arising from processes on N2 (Stevens et al 2011). The model is called AURIC, the Atmospheric Ultraviolet Radiance Integrated Code. This model will be used for interpreting Pluto atmosphere data taken at UV wavelength with the New Horizons Alice instrument.

If Pluto was not already an exotic place to visit with all the predictions about its formation, its interior, its surface, it surface-atmosphere interaction, its composition, etc., it certainly will prove to be an amazing place if any or all of these predicted upper atmosphere and mesosphere molecular species, ions, and high energy particles are measured with the New Horizons spacecraft!